UC San Diego Researchers Develop New Method to Predict Breast Cancer Spread

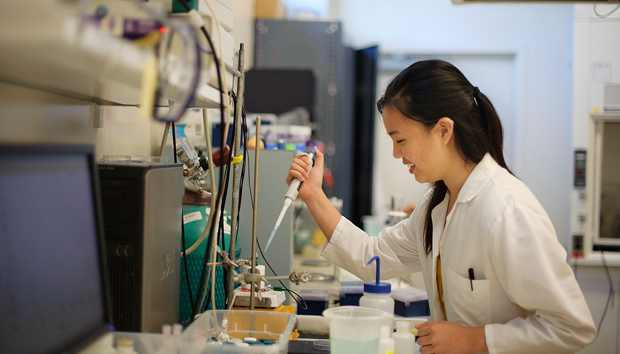

San Diego, CA – March 5, 2025 – Researchers at the University of California San Diego have discovered a groundbreaking method to predict whether early-stage breast cancer is likely to spread. By assessing the “stickiness” of tumor cells using a specially designed microfluidic device, scientists may now have a key metric to classify cancer aggressiveness and personalize treatment strategies.

The device, tested in an investigator-initiated trial, sorts tumor cells by their adhesion properties as they pass through fluid-filled chambers. Findings revealed that weakly adherent (less sticky) tumor cells were associated with aggressive cancers, while strongly adherent (more sticky) cells correlated with less aggressive cases.

What we were able to show in this trial is that the physical property of how adhesive tumor cells are could be a key metric to sort patients into more or less aggressive cancers,said Adam Engler, senior author and professor in the Shu Chien-Gene Lay Department of Bioengineering at UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

If we can improve diagnostic capabilities with this method, we could better personalize treatment plans based on the tumors that patients have.

The study, published on March 5 in Cell Reports, builds on previous research by Engler’s lab in collaboration with Dr. Anne Wallace, director of the Comprehensive Breast Health Center at Moores Cancer Center, UC San Diego Health. Earlier studies showed that weakly adherent cancer cells are more likely to migrate and invade other tissues, making them more dangerous.

Potential Breakthrough in Diagnosing DCIS

The research focused on ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), an early-stage breast cancer often classified as stage zero. While some DCIS cases remain harmless, others progress into invasive, potentially life-threatening cancer. Current clinical assessments based on lesion size and grade do not always provide an accurate prediction of cancer behavior.

Dr. Wallace emphasized the importance of this new approach:

Having a mechanism to better predict which DCIS cases will behave aggressively could hold great promise. We don’t want to over-treat with unnecessary surgery, medicine, and radiation, but we also need to intervene when there is higher invasive potential. Our goal is to continue personalizing therapy.

How the Device Works

The research team designed a microfluidic device—about the size of an index card—coated with fibronectin, an adhesive protein found in breast tissue. When tumor cells are introduced into the device, they adhere to the fibronectin coating and are subjected to increasing shear stress as fluid flows through. Cells that detach at lower stress levels are classified as weakly adherent, while those that remain attached are strongly adherent.

The team tested the device on 16 patient samples, including normal breast tissue, DCIS tumors, and aggressive breast cancers. Results showed:

– Aggressive cancer samples contained weakly adherent cells.

– Normal breast tissue samples contained strongly adherent cells.

– DCIS samples displayed intermediate adhesion levels, but with significant variability among patients.

Tracking Patient Outcomes Over Time

Study co-first author Madison Kane, a Ph.D. student in Engler’s lab, noted the wide variation in adhesion strength among DCIS patients:

Among DCIS patients, we found some with strongly adherent tumor cells and others with weakly adherent cells. We hypothesize that those with weakly adherent cells are at higher risk of developing invasive cancer and may currently be underdiagnosed.

To validate this hypothesis, the research team plans to track DCIS patients for the next five years to determine whether adhesion strength correlates with metastatic progression. If confirmed, this device could provide oncologists with a powerful new tool for treatment decisions, identifying patients who need early, aggressive intervention.

Future Implications and Collaborative Research

Engler highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in advancing this research:

Our hope is that this device will allow us to prospectively identify those at highest risk so that we can intervene before metastasis occurs.

The project was made possible through collaboration between bioengineering experts and clinicians at Moores Cancer Center and was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The research team credits shared resources, training grants, and investigator-initiated trials for driving innovation in breast cancer diagnostics.

It’s been a great partnership with Dr. Wallace and Moores Cancer Center, Engler said. Their support has been instrumental in making trials like this possible.

If successful, this device could revolutionize breast cancer screening, enabling doctors to provide earlier, more precise treatment plans and potentially save lives.